We Can Move

Weeds are overspread on the cattle pasture at the top of the hill: tar-weed, vinegar-weed and milk-weed (although not so much of this last one); all are natives and all highly unpalatable - likewise turkey mullein - to the cows that are occasionally put here to graze. There was a brief flush of non-native grasses earlier in the year, and then mustard and Erodium, but the cattle were out often enough to reduce the field to a dusty, over-grazed paddock by spring. Yet somehow this pretty (and in the case of vinegar weed, pungently aromatic) trio of weeds survived the bovine onslaught and made it through much of the summer. Now, still blooming tar weed dominates the gentle north facing rise and turkey mullein studs the ground either side of the north-south track the cattle and I take as we make our way across the field. Along the way too, stunted vinegar weed still sports its delicate blue flowers.

Recently, approaching from the south (along the track that parallels the deep ravine that becomes the western boundary of the field) with the rise forming the near horizon, a flock of Dark-eyed juncos rose up like a small cloud from the un-seen meadow: the avian mass quickly dissipated then came together again in a similar sort of vaporous formation. They had been feeding, I realized, as I chased them north in the early morning light, on the tarweed. A few days later, the entire spectacle was reprised but this time, they flew off to the west - just far enough to alight on a chaparral bush too distant to identify but close enough that I could make out the coal-black feathered eye sockets of these little brown-grey birds.

Here, on the meadow, east of the great chasmic gorge, there is a clear view west out to the Santa Ynez range as it stands up before Ventura’s coast and forms a scenic flat over which the sun and moon disappear. This morning, the almost full moon appeared as a mottled apricot for the few minutes that it hung above the jagged edge of the mountains. To the east, and at more or less the same time, the sun – the two celestial bodies in cosmic lockstep – was beginning to rise over the Santa Paula ridge. It is at such moments that this spot feels like a rostrum from which one might, with some trepidation, direct the morning’s music: coaxing the full majesty of the sun from its terrestrial lair, urging it up into the empyrean from where it can let loose its cosmic rays, destroy the ambiguities of the night, banish the moon, and unsubtly establish the incontrovertible truths of the day.

There is, in this process, a clarity that is usually less than evident in our lives, although we too are in lockstep with biological processes that will ensure our eventual decay and death. A long night, we can be assured, will follow our brief day. Exactly how much light floods into that day is, it seems, a function of the circumstances of our birth and subsequent happenstance: first we are locational victims of geo-politics and then often hierarchical casualties of our natal socio-economic milieu. We are products of our particular environment quite as much as those native ‘weeds’ are of their horticultural setting; but we can move.

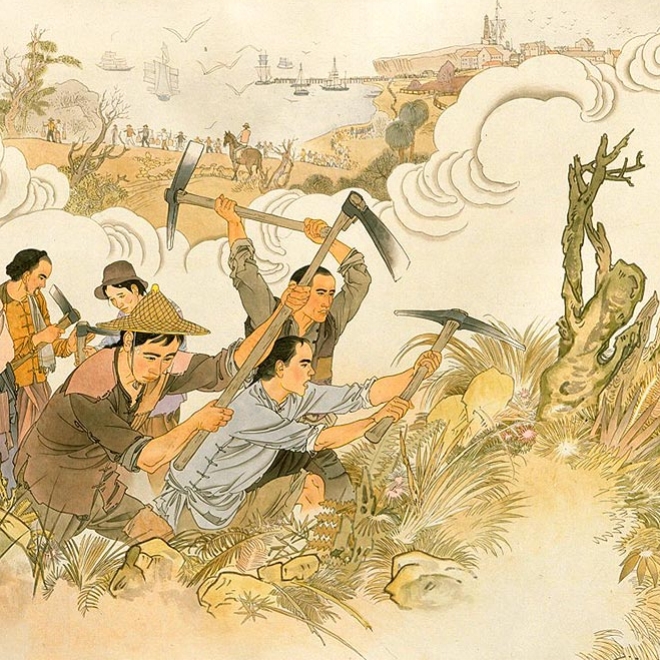

From the very beginning, humankind has done exactly that - we have left one place and sought advantage in another - and the history of California, in particular, is inextricably entwined with a long succession of arrivals from less favored homelands.

Locally, during the depths of the last ice age, from 21,000 to 18,000 years ago, sea level was 400 feet lower than at present and the beach about twenty five miles further west. The northern Channel Islands were one, known as Santarosae, and it only remained an island by virtue of the fact that it rose out of a deep channel beyond the continental shelf.

As Terry Jones and Katherine Klar point out in California Prehistory, Colonization, Culture, and Complexity, (2012), the extent of glacial ice during this period would almost certainly have precluded the initial settlement of the land from northeastern Asia. The melting of the glaciers in the warming that followed (known as the Holocene Interglacial, which continues as our current geological epoch) opened up the New World for migration from Asia, and despite subsequent dramatic oscillations in climate, made California, with its dense conifer forests, rich marine life and relict megafauna, a favorable destination for the prehistoric Asian diaspora. We can now, with a fair degree of certainty, date its first arrivals back to 15,000 BP.

The west coast of North America remained an outlier to history until the seventeenth century when the voyages of Cabrillo (1542), and Drake (1579), brought it into the realm of European politics. By virtue of Cabrillo’s explorations, Spain claimed California and considered its native peoples as subjects of the Crown, but they did not take possession of the territory until 1769, when goaded by an awareness of Russian fur trader’s interest in the area, Junipero Serra and Gaspar De Portola took hold of the country by establishing missions and presidios – military garrisons in support of the Franciscan project of Christianizing the native population while installing them as un-paid laborers, or serfs, within what they planned to be initially self-sufficient, then surplus producing communities.

The Spanish were the first of California’s modern conquerors; then Mexico, in 1821, took control as a more or less unintended consequence of their overthrow of Spanish rule (exactly three centuries after Cortes’ conquest of the Aztecs); finally, Alta California was invaded by Anglo-Americans in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was a moment of triumph for the mostly poor-white frontiersmen, many of whom were Bear Flag veterans, who rallied behind West Point educated Fremont and his successor Stockton, but their occupation predictably resulted in the devastation of the Californio, campesino and Native American populations.

A measure of the disruptive impact of the arrival of Americans can be judged by the fact that for a decade or so around the conquest, Los Angeles was the most violent place on the continent and quite possibly on the planet. John Mack Faragher, in Eternity Street, Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles, 2016, suggests that the murder rate was “comparable to that of Mexican border towns in the first decade of the twenty-first century, at the height of the violence between warring drug cartels”. He goes on to quote William Butts, editor of the Southern Californian, who in 1854, bemoaned the fact that the cultural contribution of the Americans to local culture was the introduction of “ever more formidable weapons of death and destruction”. This homicidal frenzy extended throughout the nascent state - San Francisco, still caught up in the Gold Rush, and far more populous than Los Angeles, almost equaled its murder rate.

After the onset of the Civil War, the formation of the California Brigade, to fight on the Union side, absorbed much of this psychopathic energy and when the four year paroxysm of industrial scale violence had run its course, California began a more peaceful integration into an expanding United States. In 1865, the Central Pacific Railroad hired many thousands of Chinese immigrants as the labor force for the last sections of the transcontinental line. They joined the thousands of their countrymen already in California from the Gold Rush era; despite anti-Chinese xenophobia, many stayed and more arrived until mounting pressure from poor white Americans and recent Irish immigrants (who, ironically, arrived on the newly completed railroad) led the Federal government to ban Chinese immigration in 1882.

In the decades that followed, agricultural migrant farm workers arrived in California from Japan, the Indian sub-continent, the Philippines, and increasingly, as time went on, Mexico. The great Dust Bowl diaspora saw as many as half a million poor white farmers flee the plains States in the 1930’s and settle in California. Black Americans began to arrive in significant numbers during World War II to work in the war industries.

Exclusionary immigration rules were finally overturned in 1965 when LBJ signed a number of bills that again opened up the U.S. to migration from Asian countries (several of which the American Empire were concurrently attempting to annihilate) and set generous quotas for nationalities around the world. Two years later, I was a part of the global Hippie migration that for a moment, found its locus in San Francisco’s Summer of Love.

Jonathon Gold reflects on the impact of the last sixty years of immigration into southern California through the medium of his weekly restaurant reviews, published first for the L.A. Weekly and now in The Los Angeles Times. His life and work are documented in the film, City of Gold, 2015, written and directed by Laura Gabbert. Gold celebrates the evolution of ethnic food sold from carts, trucks, and hole-in-the-wall restaurants to white-table-cloth establishments as a way of demonstrating the power of gateway capitalism - through which immigrants can establish their ethnic identities in new places by selling their distinctive cuisines to the local community and the wider population. Their service workers, many of whom have shared a similar journey to their employers, remain mired in the low wage world that such entrepreneurial ventures demand and thus find less reward in having moved.

In both Los Angeles and San Francisco, and throughout the towns and cities of California, a complex mix of cultures contributes to what in the botanical world would be called a climax community – where an intricate mix of environmental adaptations contributes to system stability. The preservation of difference, in values, customs and lifestyles is fundamental to the spirit of southern California and is greatly threatened by the neo-liberal globalism that seeks the homogenization of values congruent to its goal of asymmetrical capital accumulation. The tragedy of Gold’s food cart entrepreneurs is that their gateway capitalism tends to feed into this neo-liberalism which seeks to erode the unique qualities of community (the very foundation of disparate cuisines) in its relentless mission to blend and commodify the cultural experiences of the planet.

The cow pasture is encrusted with a dried mulch of Erodium botrys through which the native weeds still manage to emerge. From this ferruginous mat the corkscrew seeds of the invasive annual herb await the first rains of Fall to swell and drill blindly into the newly softened soil. Next Spring will see the renewal of the species’ inexorable progress in entirely colonizing the field.