No Tomorrow or Fashion Forward

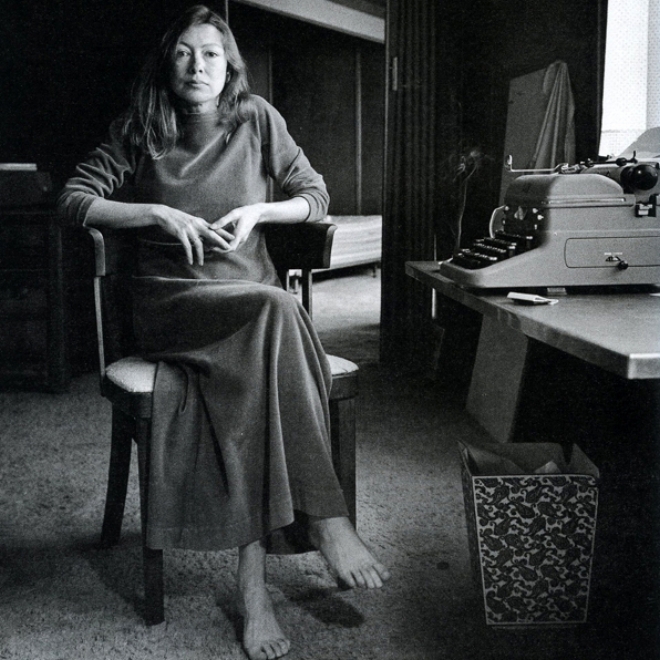

The dark subtext of the neoliberal economy, based as it is on a model of perpetual growth situated on a planet of finite resources, is that it is entirely unsustainable. This is not news. Yet in California, many continue to live as though there is no tomorrow perhaps because, as Joan Didion writes, “the future always looks good in the golden land because no one remembers the past”. This is a fine fragment of the glib, always a hallmark of the Didion canon, but writing in the seventies, she was well aware of legions of young people drawing heavily from the past in creating the Hippy lifestyle, and is shown in photographs from that era wearing the flowing long dresses that were emblematic of their culture. Today, although many of us continue to live avowedly in the present, the past has been resurrected by another cohort of loosely aggregated young people and they use their historical awareness to shine a light on the planet’s potential tomorrows.

To glance into the rear-view mirror (encompassing just this hemisphere) is to reveal past civilizations with fundamental flaws in their economic systems whose societies remained in complete denial of the day when those flaws might be exposed: where the future always looks good, until it doesn’t. We know something about these tomorrows that finally arrive, because archaeologists study them: our long-ago yesterdays, when civilizations were massively disrupted by sudden economic, societal and environmental collapse - so to begin, a jeremiad.

David E. Stuart, an archaeologist in the Southwest, and author of Anasazi America, 2014, suggests that we are now all Chacoans. By this he means that contemporary America resonates with the narrative arc of the Pueblo people who developed a successful society in Chaco Canyon, in what is now New Mexico, but which foundered, almost nine hundred years ago, on excessive attenuation of trade, income inequality and climate change.

The Chacoans devised a diversified economy which combined agriculture and hunting and gathering, which enabled them to prosper in the first millennium despite living in a desert region with less than reliable summer rainfall. Around 1000 C.E., the climatic conditions became more favorable and the Puebloans were emboldened to expand their agricultural base. Stuart writes, “Charcoan society could have used this reprieve to improve the lot of individual farmers and create incremental efficiencies, but it did not. Instead it chose growth and power”.

In their new territories they built ever larger great houses of up to four stories tall and sometimes containing more than six hundred rooms, connected to their home canyon by more than four hundred miles of roadway. Their trade network stretched from southern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico; and while the size, complexity and power of the society grew, so too did the disparity of wealth reflected in rates of infant mortality and average adult height, which varied by almost two inches between rich and poor.

Around 1090 C.E., a devastating five year drought led to widespread famine and the abandonment of many outlying farms. The Chacoan elite responded by creating vast new infra-structure projects which temporarily absorbed the un-employed farm laborers but did nothing to solve the underlying problem of agricultural productivity. A second major drought forty years later led to the unraveling of Chacoan society as more and more farmers fled their lands and joined an exodus to the uplands of the east. Stuart notes that within a generation, amidst sporadic warfare and plundering, Chacoan society had ceased to exist.

As Jared Diamond shows in Collapse, 2015, a similar process was at play in the downfall of the Mayan civilization sometime between the eighth and ninth centuries. Again, a prolonged drought, this time exacerbated by the deforestation necessary to the expansion of their agricultural lands, led to the abandonment of population centers in the central lowlands of Yucatan, leaving their cities and ceremonial sites to be swallowed up by the second growth of tropical and sub-tropical broadleaf forests.

The story of Easter Island (Rapa Nui) is almost too well known to bear repeating: suffice it to say that a combination of environmental depredations, notably a deforestation that may or may not have been connected to the transport of their giant ceremonial sculptures or moai, recurring rat plagues and the long term use of the palm forests as fuel, combined with the natural limits of their small island severely stressed the population long before the arrival of the first Europeans in 1722. Indeed, by the late seventeenth century, it is reliably reported that vestiges of a population that once approached fifteen thousand, had been tragically reduced to living in caves, eating rats and sharpening their obsidian pointed spears to ward off fractious neighbors. Whilst not quite the perfect ‘Green’ parable of a society willfully chopping down the last tree to serve the elite’s desire to out compete each other by the erection of ceremonial statuary - and suffering the consequences of soil loss and starvation - the decline of the Rapanui was clearly intimately entwined with the climate and ecology of their tiny bio-sphere.

For all our advanced technologies, it is highly unlikely that we are immune to similar environmental melt-downs: hostage to an economic system that must grow or die and living at a time of inevitable and potentially cataclysmic climate change, the possibilities for major societal disruption are clear. An increasing gap between rich and poor and the geographic segregation between the prosperous and the striving only heightens this potential for collapse. When many of our most promising youth are sold into the debt peonage of a frequently valueless college education lured by hopes and dreams seeded by the propaganda arm (comprising the government, the media and grade-school education) of a pervasive neoliberal ideology, the outlook looks bleak indeed. But out of this dire societal amalgam there has arisen a cadre of unlikely potential saviors: the hipsters.

Those who write of environmental catastrophism (and it’s a rich tradition) and its shadow of economic collapse are limning a dystopian future in order that it might be avoided. Others, in the charming small town that lies eight miles distant from my perch in the urban wildland, and throughout the planet in places inflected with a hipster sensibility, practice, or at least consume, arts, crafts and produce that are informed by a sophisticated awareness of a potentially blighted tomorrow.

They practice under the rubric of rustic modernism: ceramicists, woodworkers and weavers who deliberately eschew the glossy surfaces of high technology and employ primal techniques to shape earthy materials while others play with the detritus of civilization to create art. A friend salvages grain bags from a local craft-brewery which, artfully unraveled, make wall-hangings; and salvages drift wood from Rincon, a notable surf beach a little way up the coast, which she lashes together with sisal to create coyly utilitarian armatures. Still others hand-make soap or candles or practice permaculture. Medieval techniques of brewing, wine and cider making are revived in dank warehouses where once bright futures were imagined in distributing imported plastic consumer goods, electronic gizmos or nutritional supplements.

In these and other similar ways, this community plays out a limited version of the New Age - or the subversion of neoliberalism. Within these creative, craft and agricultural realms there are attempts to find alternatives to a system fated to end in the apocalypse of environmental collapse; but while these artists, craftspeople, cottage-industrialists and market-farmers (and many of their customers) practice alternate economic and social behaviors they do so within a prevailing and constantly enticing economic system that threatens every act that is independent of its sway - and like an on-rushing ocean often obliterates their efforts like footprints on the shore.

But their power of example remains immense: that they have assumed a position in the fashion vanguard of this country is hugely significant. On the one hand they are fully entwined in the meretricious machinations of a malevolent economic system while on the other they play creatively with the tropes of its destruction. Our future may well lie with these legions of the fashion-forward. Out of the rich soil of societal decay, this movement, of whom many are the spawn of society’s most prosperous, has arisen to offer ideas for our salvation.